Metacrisis

What is Metacrisis?

Futurists, philosophers, historians, and scientists are exploring and describing the current global condition as in a state of polycrisis. The term polycrisis describes our world as existing in many simultaneous, interconnected crises that present severe risk to the survival and well-being of both the planet and human civilization. French complexity theorist Edgar Morin first used the term back in the 1970s, and the concept became more popular among European leaders in the decade following the 2008 global financial crisis.[i] Before the Industrial Revolution and modern globalization, the average person could not imagine that humanity could destroy itself in such horrible ways as with atomic bombs and mass pollution. While disease has always been a threat, the ease and rapidity of global air travel have made the spread of pandemics and accompanying crises even faster than in previous eras. Such rapidity of travel for both humans and their pathogens presents the possibility of polycrisis. Some thinkers prefer the term metacrisis (or meta-crisis), which literally means, “beyond crisis,” hinting that we must seek some positive state of existence beyond the presence of many interrelated crises. Used in the singular, metacrisis also implies that there is a common thread running through all of these severe risks.

Researchers in the metacrisis discussion explore the interconnectedness of various crises and possible solutions— economic, political, medical, environmental, educational, and more. What kind of world can we make that survives and flourishes beyond the crises of our age? Some thinkers like Zak Stein are calling for a total re-education of people to reorient their worldview.[ii] Metacrisis research focuses on creating a new global vision that requires mass collaboration, new societal values and structures, and global governance. They claim that they seek to avoid the extremes of chaos and a tyrannical dystopia.[iii]

In the West we have reached a severe legitimation crisis on federal, regional, and local governmental levels. Can an added level of international governance mandating a radically new worldview be possible without severe violent conflict and loss of fundamental human rights? As Zygmunt Bauman explored in his numerous writings about living in liquid modernity, we wonder how we can balance the pursuit of both security and emancipation, a solid safety and a fluid, individual freedom. Will a worldview shifting toward solving the metacrisis generate a spate of wars across the planet because some regions will feel ignored by a global governing class? Will these proposals for a new world order create a quasi-religion that demands everyone’s allegiance? Critics will be quick to point out that metacrisis research may be overstating and excessively interconnecting the dots of crises that have been around for many millennia. Racism, economic hardship, famine, pandemics, and other risks have been in simultaneous existence since the dawn of civilization. On the other hand, the threat of global nuclear destruction and micro-plastic pollution are indeed unique crises in human history. This relatively new field of metacrisis will no doubt generate much discussion and anxiety in the near future.

After reading about all these crises you may rightfully sense a feeling of hopelessness and gloom. What plagues us most is not necessarily the presence of so many crises, but the volume of conflicting information to help us define and solve the issues. In the not-so-distant past, societies and communities would enthusiastically rally around a cause if there was a unified understanding of what needs to be done. Our contemporary problem is that we don’t know who to trust since we’re living in a crisis of being and knowing. In a world where everything is possible and nothing is certain, how do we really know what to believe and who to trust? Do we just stick our head in the sand or proceed on our merry nihilistic way to fulfill only what suits our immediate needs and desires? Perhaps we skeptically assume that all this depressing crisis-talk is just an excuse to promote a personal agenda.

A Metanarrative for Our Metacrisis

Christianity and the Bible assume that we need a metanarrative or grand story to resolve our inner turmoil and know how to navigate our present personal crisis as well as any global metacrisis. In its very first book the Bible presents crisis as the state of humanity. Not that we should avoid or neglect using our heads and hands to resolve the crises that afflict us, but we must first come to terms with the reality that the root cause to the crises we face are beyond mere human solutions and far above our expertise. We need a transcendent message and divine assistance from a source beyond our limited and uncertain human capacities. The Bible, both the Old and New Testaments, is a composite narrative written across a span of about 1,600 years by as many as 40 authors from various socio-cultural backgrounds across the Middle East, Europe, and Africa. Millions of its readers and believers throughout history have been strengthened by its life-giving message. It is no surprise that we modern people often struggle with understanding the Bible, but that should not deter us from reading and exploring its timeless wisdom. Most of us drive cars, fly in airplanes, use computers, and partake of the benefits of modern medicine with very minimal knowledge of how all these machines work. Experts in flight technology, digital applications, and medicine will spend a lifetime studying and exploring their fields. Investing time into learning how to live in our crisis-filled world will surely require a lifelong journey. As mentioned above, metacrisis researchers are looking for a common thread among our crises that will help us resolve threats to our planet. That common thread is mentioned in the Holy Scriptures! The Bible is much like a tapestry of dark and light threads interwoven to present a big picture of reality.

ENDNOTES

[i] Kate Whiting, interview of Adam Tooze for the World Economic Forum, “This is why 'polycrisis' is a useful way of looking at the world right now,” March 7, 2023, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/03/polycrisis-adam-tooze-historian-explains/, accessed Oct. 3, 2024.

[ii] Kyle Kowalski, “A Crisis of Crises: What is the Meta-Crisis? (+ Infographics),”

https://www.sloww.co/meta-crisis-101/#meta-crisis-definition, accessed Oct. 3, 2024.

[iii] For explanations of this global vision see David J. Temple, First Principles and First Values: Forty-two Propositions on CosmoErotic Humanism, the Meta-Crisis, and the World to Come (Austin, TX: World Philosophy and Religion Press, 2024), 32-34, 54-55.

Crisis After Crisis

Crisis as a Multi-Headed Hydra

The crisis-laden situation of our world may be compared to the Greek myth about the multi-headed Hydra of Lerna. Every time we cut the head off of one crisis, the head of a new one grows in its place! The ancient myth depicts the severe difficulty we face in the effort to conquer evil. Our crises are like the Hydra’s heads, interconnected and self-generating from the same organism.

Contemporary German philosopher and social theorist Jürgen Habermas has described the integrated nature of the crises of modern capitalist societies in his book Legitimation Crisis. While critics have made justified challenges to his writings, Habermas draws some noteworthy observations on the idea of crisis. He begins by comparing a society to a medical patient. The human body possesses various internal systems that work together to maintain normal life functions— respiratory, circulatory, neurological systems, etc. Each system influences the others, and if one is malfunctioning the body either adjusts itself to maintain homeostasis, or it experiences death. The situation becomes severe when more than one system breaks down. The unfortunate demise of the patient when too many systems malfunction.[i] In our personal lives, families, schools, local government, and place of employment we may wonder if we can survive if things continue on the current trajectory.

Like a human body, our society also contains some vital, interrelated systems. Habermas proposed that a crisis might arise in the political, economic, or socio-cultural systems. A political crisis may arise due to economic or socio-cultural reasons, or an economic crisis could arise from socio-cultural factors. When such crises arise, people may lose respect for the competency of their leaders, and then a legitimation crisis occurs. As an idealist, Habermas believed that rational dialogue in the public sphere will bring us closer to solutions for our crises. He talked about our lifeworld, which is basically our everyday life wherein we work and play. It's where we live out our current systems of education, economy, and politics. He idealized that rational people in society with shared values can discuss their problems and bring resolutions to the struggles of everyday life. Habermas recognized that the systems may become ends within themselves rather than fostering improvements and solutions for the people.

Habermas’s ideal sounds promising, but are we able to really make it work? Unfortunately, our lifeworld has become so disrupted that even when we speak the same language rational discussion is hindered. It is no wonder that a spirit of mistrust dominates us. Do we and our leaders really seek rational solutions with pure intentions, or are we seeking to maintain our personal grip on wealth and power? Are the human mind and moral spirit capable of discussing, discovering, and executing real solutions to our crises?

As so many of our social institutions are experiencing disruption our entire lifeworld feels like it is disintegrating. Modern Western thinking has ingrained in us the instinct to deconstruct our foundational values as well as the support structures of marriage, family, church, and government. We are taught to atomize every category of understanding reality and have forgotten to view our lives as an integrated whole. Using Habermas' metaphor of the human body, our major support systems in society are in such a sick condition that we feel like the body of our society may be spiraling downward toward an impending death. Society is sick and dysfunctional because we as individuals are spiritually sick. The flaws of society run deeper than the organizational character of our various systems. A biblical worldview guides us to realize that the human soul needs a reset. First, we need an internal renewal of heart, mind, and character.

[i] Jürgen Habermas, Translated by Thomas McCarthy, Legitimation Crisis (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 1988), 1-2. The English title of his originally German text, Legitimationsprobleme im Spätkapitalismus, literally translates as Legitimation Problem in Late Capitalism. In context the English word “crisis” better portrays the title than simply “problem.” Some scholars classify Habermas as belonging to the Marxist Frankfurt School of thought, while others categorize him as departing from it due to his emphasis on dialogue and his recognition that the economic sphere is not the only cause of societal dysfunction.

Lost in Liminality

Lost in Liminality

by Keith Sellers

Liminality is an existence between two states, destinations, or stages of existence. Perhaps a pre-teen is not really a young child, but not quite yet an adolescent. We may be traveling from one airport to another that is so far away that we must stopover at another city before arriving at our final destination. While we wait to board the second flight we may be overcome by feelings of anxiety, frustration, or impatience, but at least we know where we came from and where we're going. In our current state of humanity, we're not sure anymore where we have come from, nor where we are now. The only thing that is certain is that we don’t know where we'll end up! While we believe that we have a nearly unlimited number of possibilities and freedom to pursue whatever we please, we feel lost in our liminality. Here on planet earth, we live in a state that exists between heaven and hell, between blessing and curse. Our lostness creates an ominous sense of hopelessness and spiritual nausea.

In 1893 Norwegian painter Edvard Munch created a now famous piece called The Scream. This iconic work which appeared in four versions, as painting and pastel, shows a person holding the sides of his face with both hands as the setting sun's rays create blood red hues. Munch wrote about his feelings that inspired this work,

One evening I was walking out on a hilly path near Kristiana-- with two comrades. It was a time when life had ripped my soul open. The sun was going down-- had dipped in flames below the horizon. It was like a flaming sword of blood slicing through the concave of heaven.[i]

In his journal notes Munch claims that he audibly heard the scream in nature.[ii] According to J. Gill Holland, the place of the figure in the painting was near a slaughterhouse and a mental institution that overlooked the fjord in Kristiana, now called Oslo. Passersby could actually hear the cries of the unfortunate occupants of these buildings.[iii] As a five-year old, Munch lost his mother to tuberculosis, and then later as a teenager his sister died. In the face of such painful loss, his father struggled with bouts of depression. Munch's Scream strikes a chord in the heart of everyone who has ever felt such inner turmoil. It is the scream of both nature and the human heart.

Art historian and curator Jill Lloyd who works at the National Gallery of Oslo commented in a BBC piece about the meaning of Munch’s Scream,

It presents man cut loose from all the certainties that had comforted him up until that point in the 19th Century: there is no God now, no tradition, no habits or customs – just poor man in a moment of existential crisis, facing a universe he doesn’t understand and can only relate to in a feeling of panic.[iv]

Over 125 years later in our chaotic era, we feel as if we are in a very similar existential crisis. We may sense that all of our foundations for life have been torn away. Many Scream-based memes and emojis appear in digital media help us express this common angst. Lloyd explains Munch’s contemporary relevance, “That may sound very negative, but that is the modern state. This is what distinguishes modern man from post-Renaissance history up until that moment: this feeling that we have lost all the anchors that bind us to the world.”[v] Where do we rediscover the lost anchors that reconnect us to our world? We may not audibly scream or outwardly gesture panic like the figure in Munch’s art, but we may likely feel that same frustrating hopelessness.

We who live in an era of post-postmodernity are facing an intensely fluid world. We don't know who we are and how to proceed forward. We now live in the world that Nietzsche's madman predicted,

"Whither is God?" he cried; "I will tell you. We have killed him ---you and I. All of us are his murderers. But how did we do this? How could we drink up the sea? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon? What were we doing when we unchained this earth from its sun? Whither is it moving now? Whither are we moving? Away from all suns? Are we not plunging continually? Backward, sideward, forward, in all directions? Is there still any up or down? Are we not straying, as through an infinite nothing?[vi]

In the West we jettisoned the foundations of our Judeo-Christian roots to embrace our own rationality and idealism. The Industrial Revolution gave us more advantage over space and time so that we can more accurately predict arrival times and costs relating to global travel. Our bodies can go more places faster, but our souls are lost in a liminality between unknown realms. We believed that our modern quest for certainty was going to produce a new and better world without dependence on any deities. As almost every sphere of knowledge increased, we imagined that we could predict, control, and guide our lives according to our liking.

We hoped that we could make a better planet through our technology and international alliances, however, World War II and the demise of Western colonialism woke us up to the failures and frailty of human progress. Some of us still doggedly believe that we're still moving forward. While we certainly have progressed in technology, our ability to resolve our ongoing crises is surely in question. Eventually, many of us wearied of modernity’s naive realism, so we yielded our facts and boundaries to a gross subjectivism and radical individualism. At a young age many of us heard from our parents and teachers, "You can be whatever you want to be!" When we grew up, we were punched on the jaw by the hard hook of reality that we never saw coming. As educated people of the West who have experienced more creature comforts than any civilization which ever lived before us, we are now staggering back and forth between two naive paradigms of thinking— modernity’s naive realism and post-modernity’s naive idealism. The Book of Genesis and the Bible as a whole provide a more realistic worldview and a relational realism that help us rediscover who we were meant to be in our relationships with God, other people, and the creation. The Bible’s message is simultaneously realistic and inspirational, hopeful and frightening, guilt-inducing and spiritually cathartic. It challenges our cognitive assumptions, our emotions, our established habits, and whatever behavioral norms we may have invented. The Bible still speaks to humanity no matter what stage or condition may characterize us.

ENDNOTES

[i] Munch, Edvard, J Gill Holland ed., The Private Journals of Edvard Munch: We Are Flames Which Pour Out of the Earth (Madison WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2005), section 34, Kindle Loc. 1147.

[ii] Munch, Edvard, Kindle Loc. 1157.

[iii] Munch, Edvard, "Introduction," Kindle Loc. 88.

[iv] Alistair Sooke, “What is the Meaning of The Scream?” From BBC Culture, March 3, 2016, https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20160303-what-is-the-meaning-of-the-scream.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science, trsl Walter Kaufmann (New York: Vintage Books, 1974), 181.

Moral Inversion

Moral Inversion in Modernity

by Keith Sellers

Hungarian-British polymath Michael Polanyi observed the spiritual, moral, and social devastation of Europe during the era of the two world wars. In his book The Logic of Liberty, Polanyi explored the debilitating effects of both Nazi and Communist totalitarianism on the progress of scientific inquiry. As a Nobel prize winning chemist, he was deeply concerned when authoritarian movements hindered the progress of science. He observed that the morally bankrupt nihilists of his day evolved through a process that he called “moral inversion.”[1] After jettisoning Judeo-Christian values, European society embraced a Nietzschean individualism that formed a spiritual vacuum in the hearts of younger generations. This spiritual emptiness led many people toward dangerous, collective movements. When the Nazi movement spread throughout Germany, Polanyi left his teaching position at Kaiser Wilhelm University and fled the country because he was of Jewish origin. His relatives and European contemporaries experienced the rise of oppressive Stalinist and Nazi movements. Both movements were similar in their promotion of social uniformity, totalitarianism, and violence. The Enlightenment’s individualism and rationalism fostered a secularized Christian faith, which devolved into an apolitical nihilism that ridiculed the hypocrisy and failings of religion. Since humans are social and spiritual creatures the apolitical nihilists embraced a political nihilism to work out their lack of beliefs and commitments. Polanyi noted that nihilistic attitudes in politics brought bloody disruptions to all spheres of European society and other regions of the globe via the radical ideals proposed by fascism and communism.[2]

The proponents of Marxist materialism in effect created a quasi-religion through which they embraced a pharisaical hubris coupled with an eschatological hope for a future economic utopia. Polanyi observed a profound internal conflict in the modern era,

Modern thought is a mixture of Christian beliefs and Greek doubts. Christian beliefs and Greek doubts are logically incompatible and the conflict between the two has kept Western thought alive and creative beyond precedent. But this mixture is an unstable foundation. Modern totalitarianism is a consummation of the conflict between religion and scepticism.[3]

Our skeptical spirit prevailed, but we still struggle to root out our moral sensitivity and need for some kind of spirituality. Polanyi realized that the totalitarian movements of his day combined both “moral passions” and “materialistic purposes."[4] Christian spirituality and its undergirding hope for a better world with justice for all was rejected and turned upside down for a material utopia. Passion for God and humanity was replaced by a violent pursuit of materialism on a global level.

The moral inversion of fascism and communism transformed sophisticated European hedonists into hellbent manufacturers of human destruction. Those who sought to create a new world order, a superior race, or an economically just utopia actually made our planet an experiment in creating record-breaking numbers of human casualties in the previous two world wars. Now we hope and pray that we never again experience such a catastrophic global conflict, especially with even more advanced nuclear weapons available all over the planet. We are quite capable of killing even more people faster than the two world wars combined. With our advanced technology we can create dystopian totalitarian societies on a global scale.

The Western experience of moral inversion is not exclusive to the West, but it is rooted in ancient history. It is rooted in Eden. The Book of Genesis describes humanity's first great moral inversions that have influenced every human, tribe, and civilization to this day. Old Testament theologian Walter Kaiser observes three major crises in the Bible's very first book-- the fall, the flood, and the failed Tower of Babel.[5] These were the first three moral inversions that have plagued humanity for many millennia. If we fail to address these inversions in our time we are doomed to further escalate the state of crisis for all of humanity.

ENDNOTES

[1] Michael Polanyi, The Logic of Liberty (Indianapolis, Liberty Fund, Inc, 1998), 131.

[2] Polanyi, 131-33.

[3] Polanyi, 135.

[4] Polanyi, 135.

[5] Walter C. Kaiser Jr., Mission in the Old Testament: Israel as a Light to the Nations (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2000), 16.

First Steps for Lay Leaders Left Behind

As a missionary serving with WorldVenture for 21+ years, my ministry in Hungary has involved evangelism, teaching, church planting and rejuvenating struggling churches. There I have filled pulpits for small churches in several denominations— Baptist, Brethren, Methodist, Reformed, and Lutheran. Whenever I returned it was usually for a period of weeks and sometimes a few months. In 2015 my family returned to the States for an extended home assignment, and during that prolonged stay I experienced reverse culture shocks. Most alarming was that during my travels through U.S. cities, I noticed many church buildings in need of serious renovation, scantly attended, and others converted into businesses. Some financially partnering churches had declined severely, and a few disappeared altogether.

What happened here in the USA? Church revitalization expert Thom Rainer estimates that over 150,000 American churches suffer from institutional sickness. (1) Often these sick churches find themselves without a pastor and are struggling to gain a foothold. Most publications address the issue from the clergy’s perspective, while ignoring the reality that the lay leaders are often left behind to run the church. The remaining lay people are like hikers injured on a lonely trail with no guide or first aid. So, what should the layperson do in those desperate times? The lay leader must resolutely take specific steps, however imperfect the foot holding, before the church slips so far that it cannot ever recover.

Take Leadership: a quick focus

The Apostle Paul admits in the early verses of his letter to Titus that some things were left undone on his previous missionary journey, namely the appointment of capable leaders (Titus 1:5-9). Paul knew that qualified leaders, both lay and pastoral, are important for the local church. Those who remain in a struggling church without a pastor must quickly take up the responsibility to lead the church and find a pastor.

The painful transition period, which could take well over a year, will present many challenges. Lay leadership must not hesitate to initiate honest communication with the congregation and make intentional efforts at corporate cohesion and confession. They must listen as they communicate with confused and disappointed church members. If they are at fault for the pastor’s premature departure, they will need to confess and apologize to members. Also, they must strive for immediate consolidation of both human and financial resources. Most likely, more people than just the pastor left. Not only will lay leadership need to find someone to fill the pulpit, but they may also need to find someone to lead worship, work the nursery, clean the toilets, pay the bills, and much more.

Because they may feel that they were “burned” by a previous leader, the laity may be sincerely reluctant to seek a new pastor. This shyness to follow a leader happens in big and small churches. Some churches may be tempted to just do the ministry on their own without ever seeking a pastor again. Some go this route for a couple of years and then decide to look for a pastor, while others will go indefinitely without a shepherd. In either case, the local congregation will suffer, lose ground, and lack direction if a senior leader remains absent. The smaller, struggling church in tight financial circumstances may need to select a capable bi-vocational pastor. Even those congregations, which have a more "primitive" church polity need someone with leadership giftedness to provide wisdom, vision, and guidance.

During transitional periods the laity must honestly evaluate the congregation's situation, and then take the necessary steps to appoint a small pastoral search team according to the church’s constitutional and/or denominational requirements. They will need to assign pulpit supply or hire an interim pastor, as well as network with other churches for ideas and personnel. The pastoral search committee must study and consult to determine what kind of leader the congregation needs to regain its foothold and move forward. A temptation exists to seek a pastor according to one’s personal preference and not according to the needs of the entire congregation and community.

Seek Outside Counsel: a broad focus

Much of the New Testament was written as advice to churches from outside experts like Paul, James, John, Peter, and Jude. While Paul did have some authority and relationships with people at the various churches he addressed, those individuals and congregations still had a measure of autonomy to accept or reject his wisdom. He was not a local, but he had extensive wisdom and broad experiences to draw from as he sought to encourage, correct and redirect churches in Rome, Corinth, Philippi, Ephesus, Colossae, Galatia, and Thessalonica. He not only wrote to them but made plans to visit and address specific problems in these churches (Acts 15:36, I Cor. 16:5, II Cor. 2:1, 13:2). Wise counselors can give us a panoramic view of the world beyond the problems of our town and our church.

Outside wisdom, networking, and consultation will help the declining church to recognize its sickness, guard against continued losses, and see the potential for the future. A church's regional denominational office may recommend or require a consultant. If the lay leadership of an independent or non-denominational church needs assistance they must network with other likeminded churches in the area or find a trusted and experienced pastor to give them advice. Sometimes a nearby seminary or Bible college can provide some expertise. Online Christian employment services like Vanderbloemen.com or churchstaffing.com provide tips for both the church and the ministry seeking pastor.

Seeking advice from outsiders can be humiliating, but it is a necessary task. If our car breaks down with a flat tire, we may not seek assistance and try to solve the problem on our own. Most likely we will succeed with a minor setback like a flat tire, but if we continue to have flat and unevenly worn tires we may be experiencing symptoms of repairs that we are not capable of fixing. Such is the case with many struggling churches. They need someone who has seen and solved this problem in other churches. Most likely, other churches have sailed the same perilous storm. Hiring a consultant can be expensive and admitting that one’s church has problems is humiliating, but this is a vital first step to survival.

Unfortunately, a declining church may have certain members who just refuse to listen to the wisdom of an outsider. Sometimes an individual or family within the congregation has dominated the life of a church for an extended period. They may hinder outside influences for positive change. John in his third epistle denounces a fellow by name for selfishly dominating a church and running off other leaders,

I have written something to the church, but Diotrephes, who likes to put himself first, does not acknowledge our authority. So if I come, I will bring up what he is doing, talking wicked nonsense against us. And not content with that, he refuses to welcome the brothers, and also stops those who want to and puts them out of the church (III Jn 9-10, ESV).

Dealing with destructive personalities may perhaps be the most formidable obstacle and challenge to a church’s revitalization. Additionally, churches tend to view their problems from their own narrow regional perspective. Often, they do not even know that they have a problem because they have been dysfunctional for such a long period of time. Solutions and coping strategies may exist which were never thought of by the local leaders.

A wise counselor will realize that not every outside solution used somewhere else will help in the local context due to unique cultural, economic, and spiritual factors. Some novice pastors may recommend a particular model or method, which they mistakenly think will solve the church’s woes. Such silver bullets only work in tales about slaying werewolves. Simply buying a projector, changing the music, and designing a website will not suffice. The lay leadership must seek advice from many sources. King Solomon gave advice to rulers of ancient kingdoms, which is applicable to churches as well, “Where there is no guidance, a people fall, but in an abundance of counselors there is safety (Proverbs 11:14, ESV).”

Expert counsel can help the church recognize its unique giftedness as well as the socio-economic shifts, which have occurred in the area since the church was established decades ago. Like a human body a declining church may have complexly interrelating comorbidities that hinder growth. Not only may the church body suffer from spiritual illnesses, but other issues may need attention-- subculture, building arrangement, organizational structure, and constitution. A church, which was established many decades ago was most likely comprised of members of similar ethnic, economic, and social backgrounds. Now years later the aging and dwindling church membership may not match the demographics of the surrounding neighborhoods. An experienced outsider will help the church detect these cultural shifts and see what potential the church has to survive and revitalize in its present environment.

Promote Unified Prayer: an upward focus

The church in transition must engage in robust corporate prayer to gain a Spirit led upward focus. During the time between Christ’s ascension and Pentecost, and even after Pentecost, the Jerusalem Church was avidly engaged in congregational prayer. Luke records the church as experiencing power for effective ministry after they participated in intense times of prayer. While the setting of Acts was certainly a unique time in Christian history the book does present examples for succeeding generations to follow. Theologians may rightfully debate the descriptive versus prescriptive character of the book, but prayer is certainly a normative practice for believers of any era. Luke reiterates in the Book of Acts that effective church ministry results from unified prayer. Both prayer and unity are frequent themes in the Book of Acts, especially as conveyed in the Greek term homothumadon, a favorite adverb of Luke the writer of Acts (1:14, 2:1,46, 4:24, 5:12). Luke uses this term ten times in Acts. Homothumadon is translated as “one accord” (A.V.), or “one mind” (NASB) or simply as “together” in several versions. The word depicts not just the physical state of being together, but the unity of their hearts and minds as well.

In Acts 1:14 the term is used to describe the unity of the praying disciples who were obeying Christ as they waited in Jerusalem for the gift of the Holy Spirit. In Acts 2:1, which relates to the same gathering, the Holy Spirit comes upon the disciples who continued to pray together. In Acts 2:46 the Christ followers are with “one mind” meeting in the temple where they were praying, breaking bread, and listening to the Apostles’ teaching (2:42). After Peter and John were summoned before the Sanhedrin and beaten for teaching in the name of Jesus Christ the disciples meet once more to pray aloud “with one accord” (A.V., NASB). Prior to receiving their saintly status in later centuries Peter and John were merely uneducated laymen in the eyes of Jewish religious leaders. When the Sanhedrin or Jewish Council summoned Peter and John they considered them as “unlearned and ignorant.” When Peter and John returned to a gathering of believers, they engaged in corporate prayer asking God for boldness in their witness (Acts 4:23-31). Even though the early Christians were under severe pressures of persecution and poverty, the Holy Spirit gave them boldness to declare the resurrected Christ and a holy persuasiveness to draw others into becoming followers of the Way. After times of prayer and fasting the Holy Spirit empowered them to select leaders, to evangelize, and to receive guidance for the next steps of ministry. Prayer enhanced their unity and resulted in continued growth of the church. Once again, the term homothumadon appears in 5:12 describing the gathering of believers under Solomon’s Portico. A result of their Spirit led unity was that “more” were added to the church (5:15). Church leaders, both lay and professional, must unite the members with passionate and intentional times of group prayer. Prayer will prepare and empower the congregation to engage in working with the new pastor, not against him.

What is Contextualization and Is It Really Biblical?

Contextualization is a term that missiologists, aka teachers about Christian mission, use to describe effective Gospel communication. Basically speaking, this term refers to the Christian communicator's effective expression of the message of God to people of other cultural settings. Underneath this concept resides the intention of creating a specific understanding and response from the listener. The Christian communicator desires that the receptor or listener understand and obey God's will as taught in Scripture, experience personal redemption and transformation, and in turn effectively express that message to others.

We all do contextualization everyday whether we realize it or not. Whether we are a Christian preacher, teacher, evangelist, VBS worker, childcare worker, musician, artist, web designer, or videographer we are communicators with an important message to give to a specific era, subculture, age group, language, or ethnicity. At one given moment we might talk with our three-year-old, and the next minute, we might pick up the phone to talk with our lawyer. We don't use the same vocabulary and tone of voice in both conversations, but we subconsciously switch gears to speak in a way that makes sense for the listener and the topic at hand. In such a case we could say that we have mastered the practice of contextualization, especially if you are a mother with a degree in law. In other contexts, with other kinds of people, we might find ourselves struggling to understand as a listener and express our thoughts as a communicator. Some Christian preachers are deathly afraid of the term, yet at the same time are practicing it every week.

Fear of the concept may stem from misunderstanding, so some basic explanations are necessary to dispel those fears. If we read the Bible with an open mind and heart, we will discover that the Bible itself is a compilation of contextualized books written by authors who desired to communicate to a specific people, in a specific place, at certain point in time, and in an ancient language. Both the medium of Scripture and its message embody and engage in contextualization.

In past decades only a few scholars addressed the topic of contextualization within the medium and message of Scripture. In 1978 missiologist Charles Kraft emphasized the importance of comprehending contextualization on the basis of Scripture, “Contextualization of theology must be biblically based if it is to be Christian” (Charles H. Kraft, ”The Contextualization of Theology,” Evangelical Missions Quarterly, January 1978, 14:36.)

Others have also expressed the need to address contextualization from a biblical perspective. For example, H.D. Beeby notes, “the more we reclaim the Bible as a whole, the more we see the canonical scriptures as providing a missionary mandate, a missionary critique, and a missionary objective” (H.D. Beeby, Canon and Mission, Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 1999, 29).

Leading Evangelical Christian scholars have offered many definitions of this difficult concept. Here are a few below with the author's name and sources referenced.

Dean Gilliland

Gilliland defines the meaning of contextualization in theology:

True theology is the attempt on the part of the church to explain and interpret the meaning of the gospel for its own life and to answer questions raised by the Christian faith, using the thought, values, and categories of truth, which are authentic to that place and time.

Source: Dean S. Gilliland, ed. The Word Among Us: Contextualizing Theology for Mission Today. (Dallas, TX: Word Publishing, 1989), 10-11.

David J. Hesselgrave and Edward Rommen

Evangelical missiologists Hesselgrave and Rommen define contextualization as

. . . the attempt to communicate the message of the person, works, Word, and will of God in a way that is faithful to God’s revelation especially as is put forth in the teachings of Holy Scripture, and that is meaningful to respondents in their respective cultural and existential contexts.

Source: David J. Hesselgrave and Edward Rommen, Contextualization: Meanings, Methods, and Models (Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 2000), 200.

A. Scott Moreau

Steering the term towards a holistic direction, Moreau defines contextualization as

the process whereby Christians adapt the forms, content, and praxis of the Christian faith so as to communicate it to the minds and hearts of people with other cultural backgrounds. The goal is to make the Christian faith as a whole—not only the message but also the means of living out of our faith in the local setting—understandable.

Source: "Contextualization: From an Adapted Message to an Adapted Life, " A. Scott Moreau, in The Changing Face of World Missions, eds. Michael Pocock, Gailyn Van Rheenen, and Douglas McConnell (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2005), 323.

Expanding on the breadth of a holistic contextualization Moreau defines it in a more recent text.

Contextualization happens everywhere the church exists. And by church, I'm referring to the people of God rather than to buildings. Contextualization refers to how these people live out their faith in light of the values of their societies. It is not limited to theology, architecture, church polity, ritual, training, art, or spiritual experience: it includes them all and more.

Source: A. Scott Moreau, Contextualizing the Faith: A Holistic Approach (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2018), 1.

Dean Flemming

I take contextualization, then, to refer to the dynamic and comprehensive process by which the gospel is incarnated within a concrete historical or cultural situation. This happens in such a way that the gospel both comes to authentic expression in the local context and at the same time prophetically transforms the context. Contextualization seeks to enable the people of God to live out the gospel in obedience to Christ within their own cultures and circumstances.

Source: Dean Flemming, Contextualization in the NT: Patterns for Theology and Mission. (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2005), 19.

Jackson Wu

Wu sees the concept as a process involving Scripture and culture, "Good contextualization seeks to be faithful to Scripture and meaningful to a given culture."

Source: Jackson Wu, One Gospel for All Nations: A Practical Approach to Biblical Contextualization (Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 2015), 8.

To sum up the observations of these scholars we conclude that contextualization is biblical, holistic, dynamic, powerful, meaningful, Spirit-led, and sometimes difficult. To appreciate the beauty of the New Testament as a contextual document one should read and study Dean Flemming's work referenced above, Contextualization in the NT: Patterns for Theology and Mission. Proper contextualization is anchored on the truths of Scripture and is adequately dynamic to address the needs of different cultures. Because God created humanity in his own image and gave us the Scriptures to address the need of humanity's redemption, we can have confidence in the content of the Scriptures to address that need.

At the same time, we should follow the Bible's example of recontextualizing older Scriptures, which sets the precedent for our need to recontextualize God's message. The Scriptures are filled with a plethora of quotations and references to previous Scriptures. Here are a few examples -- numerous OT quotes and metaphors in the NT; the reapplication of the Abrahamic Covenant in the teachings of Jesus, Romans, and Hebrews; the repetition and reapplication of the Ten Commandments in Deuteronomy, the Gospels, and the Epistles. Why are older Scriptures repeated in both the OT and NT? Because God knows that his people of all eras and cultures have universal needs as well as live in unique, dynamically changing contexts. Yes, there is always the danger of over-contextualization or syncretism, but to not engage in contextualization eventually leads to syncretism and meaningless religious practice.

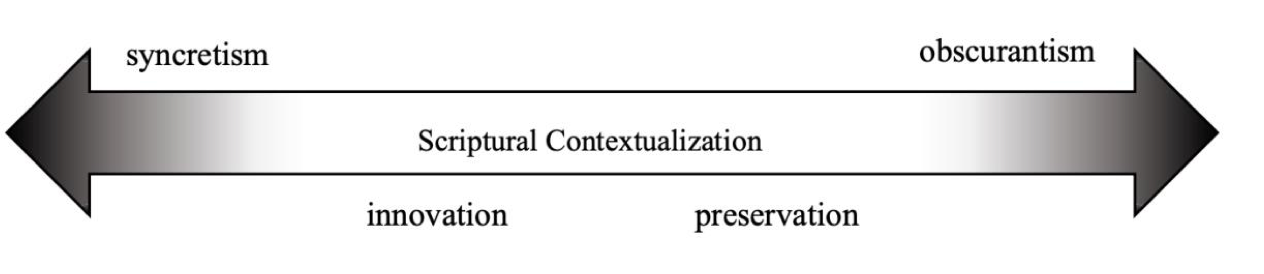

The figure below may help in understanding the concept as a dynamic process.

The gradient two-way arrow depicts the continuum of biblical contextualization. The extremes to avoid are syncretism and obscurantism. Obscurantism occurs when the communicative expressions are so culturally distant or outdated, that disciples and inquirers cannot adequately comprehend certain teachings of the Christian faith. They may better comprehend those teachings if we modify the way we express them. A clear line between the boundaries of syncretism, obscurantism, and biblical contextualization does not always exist.

While cardinal teachings and universal moral values of the faith fall in the middle or white region, some practices may be on the edge or in the fuzzy, grey area of classification, or they have entered the darker extremes on the continuum. Sometimes practices which are obscure or nostalgic may once again become effective tools of biblical communication, especially in times of extreme societal or technological shifts.

The extreme fluidity of contemporary life in a Western culture that values change makes the task of contextualization even more challenging. The condition of liquid modernity intensifies our challenge. By liquid modernity, I mean that we are living in an era that mixes elements and thinking from ancient, modern, and postmodern eras. The numerous works by and about Zygmunt Bauman who popularized the concept explain the idea in greater detail (Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity, 2000). Other factors which contain blessings and challenges include globalization, mass immigration, digital technology, and the abundance of intercultural exchange of ideas and products. The recent Covid-19 pandemic as well as accompanying political polarization have also highlighted the needs and challenges of contextualization. The postmodern idea that power produces knowledge rather than vice versa remains a major issue. Finding balance between the need for both security and freedom will also be a major issue for years to come. While we may not have the answer for every contemporary issue, we do have an anchor in Christ the Living Word as well as in the Scriptures, the written Word. The eternal life-giving Logos, who is Christ possesses the knowledge, power, wisdom, and redemption that all of humanity needs. Only the Logos can provide the contextual message for all people of every age.

Charting the Course in Dangerous Seas: Churches in the Cross Currents

The cross currents of modernity and postmodernity have forced many a church vessel off course, and some have become shipwreck like the individual lives of Hymenaus and Alexander (I Tim. 1:20). Some church leaders do not understand why so much change and chaos is happening in their church, their members' families, and their communities. Because contemporary western societies are so fluid and dynamic Christian leaders must repeatedly navigate the vessel of the church in uncharted waters. Using Marx's phrase, "melting of all solids,” Zygmunt Bauman's seminal work, Liquid Modernity, describes western society as not having totally thrown off modernity for postmodernity, but he maintains that society flows like liquid in and out of the two paradigms. Bauman describes our situation with the term "liquid modernity." His book describes contemporary society as struggling with the themes of emancipation (freedom), individualism, community, time, space, and commodification. Modernity and postmodernity are difficult terms to describe. Some thinkers define the terms as feelings, moods, perspectives, or philosophical paradigms of thinking. They have affected politics, art, theology, social relationships, clothing, music, economics and almost every area of European and American lifestyle. When I think of modernity I think of Batman, the consummate human blend of intelligence and athleticism, who utilizes high tech gadgetry in a modernized city full of skyscrapers. He may appear as a highly cultured and respected billionaire in his fine suit and tie or as the daring pale white crime fighter racing in his Batmobile to defeat the next criminal. Modernity embraces the values of institutions, programs, systems, orderly protocol, science, and high culture as containing the right answers or showing the way to a better life. When I think of postmodernity, I envision a bearded hipster artist with piercings and minimalist, torn clothing protesting a big institution's abuse of power and privilege. Postmodernity embraces the values of community, simplicity, nature, raw transparency, and multiculturalism. Describing the two terms in a child's perspective, modernity's cartoon characters approximated real, lifelike animals and people while postmodernity cartoons are two dimensional, flat, and absurdly proportioned. Yes, this description of the two terms is limited, but if you want to know more read a philosophy book or find a good video online.

Bauman's perspective helps us understand why the younger generation loves smartphone technology and minimalist styles, but despises modernity's institutionalized church, highbrow music and culture, and hierarchies. The older Baby Boomers are slow to engage in the latest computer technology and apps, but wallow in the once praised models of beauty, titles, institutions, and bureaucratic programs. Each generation picks and chooses different elements from modernity and postmodernity. Bauman's term "liquid modernity" helps us understand why the bankers, business executives, politicians, and some Christians still wear suits and professional attire while computer geeks, hipster artists, and other Christians will wear whatever crosses their screens that given season. The clash of the two worlds of postmodernity and modernity helps us see why in some spheres of Western society rules and complex protocol are abundant while in other areas of life a Wild West anarchy prevails. We may have too many rules or not any at all. The permanent print of the Gutenberg world clashes with the spontaneous and ever-changing digital Google reality. The lines have been blurred between reality and fantasy, between a practical realism and an idealistic imagination. Such is the case in the so-called reality television shows. We used to know when we were in fantasy and reality, but now we are lost at sea as the waves crash from both sides. Some thinkers say we must return to the old debates between Plato and his young disciple Aristotle, ideas vs material reality, but that is another topic.

Bauman claims that people and institutions must become light and nimble, or they will drown trying to hold on to everything that they can access. Such is the plight of older generations holding on to every electronic product ever produced since the 1970s. You just cannot hold on to everything from modernity. Bauman also warns that societies must hold on to some anchor to steady life in the rushing waters. While I certainly do not subscribe to any neo-Marxist political stance that Bauman may hold, as a secular sociologist he has made some very astute observations for Christian leaders to consider. Christianity has solid truth to offer those disappointed in the solids of modernity and the fluidity of postmodernity. For some years Christian thinkers have warned about the dangers of postmodernity. At the same time, we should beware of the dangers of an arrogant and outdated modernity. Attempting to bring balance to the two worlds, D.A. Carson recommends a "chastened modernism and a 'soft' postmodernism" (Christ and Culture Revisited, 89). Holding on to everything from modernity can be like hanging on to that old 200 lb. television set with its fuzzy resolution and incompatibility to current digital technology. We hate to get rid of it because we spent so much money on it in the late 1990s. It's too hard to move out of the house because it is so heavy, and we are reluctant to pay someone to take it away.

A local church can be in the same plight as the leaders struggle with what programs, structure, music, and customs to use. Church leaders must hold on to something solid while letting unecessary things go. Some churches make the mistake of casting off their core doctrines and biblical morality as if they were just throwing out old Sunday school curriculum. Others refuse to change anything in their church, and therefore the visitor or newcomer feels like he is stepping back into a previous decade, century, or even another country. The church visitor may suffer from a cultural shock and wonders if following Jesus here requires his adaptation to a totally new culture.

From the Enlightenment and Age of Reason to recent times, thinkers and movers of western society attempted to guide and mold society into their preferred structures, institutions, and systems. Marxism and fascism attempted to produce totalitarian societies to create utopias in Europe, South America, and Asia. American capitalism clothed with Christian values attempted to project a commercialized dream and secure way of life, which is now unreachable for many among the younger generations. Denominations used to argue about which one had the best and most biblical form of church. Perhaps in the past we argued too much about lesser things, and now our churches are all just trying to survive. Our compass of truth cannot point to true North, and so we have coined new terms like post-truth and alternate facts. Modernity took humanity to the heights of industrial accomplishment and scientific knowledge, but the paradigm's bent toward arrogance, racism, disrespect for nature, and doubt in the supernatural brought humanity to the brink of destruction in the World Wars. Unfortunately, many churches and denominations embraced the same errors. Postmodern thinkers led societies to doubt the very nature of truth, and their beliefs are destroying societies by redefining morality, the nature of humanity, and the meaning of family and sexuality. Describing the emancipation of postmodernism, former Czech president and writer Václav Havel warned, "We live in a postmodern world where everything is possible, and nothing is certain." Extreme postmodern voices claimed that truth is relative to community and cultural upbringing. Without truth there is no meaning. Where meaning is lacking so is purpose.

On a positive note, postmodernism has helped western society and Christianity to once again respect nature and ethnic diversity as well as restore the possibilities of supernatural reality. Delving into quantum physics, some secular thinkers are postulating a simulation theory of the universe in which some higher being, perhaps God, simulates and regulates the universe according to a higher plan. In the new branch of science called biomimetics, researchers seek to imitate and utilize nature's design in technology under the assumption that something or someone bigger and smarter than humanity "designed" the world. Without sounding irreverent, postmodernism makes all things possible. Western Christians who have a philosophical bent toward excessive individualism have rediscovered the necessity of community in spiritual growth and understanding Scripture. While truth has been called into question by society at large, Christians now have a platform to prove the superiority of their Savior by living out truth and sharing their experiences of the supernatural Christ with a world which doubts everything. By telling their personal stories of their relationship with Christ, Christians now possess a unique advantage that was not present two decades ago. Christians can now evangelize by telling their own raw and simple testimony without resorting to a prescribed sales pitch with three or four well developed points.

In North America we must realize that we are a mission field with a unique confluence of many cultures and ideas. In some newer communities, churches are certainly thriving, while in many other areas churches are plateauing and declining for various reasons. Too often local church successes arise not primarily from conversion growth but from a geographical redistribution of the mobile masses of existing believers who moved into a new community for a job relocation or educational opportunity. In the 1980s and 1990s Christian leaders started to speak about the best models and patterns to follow for church and ministry, but in the confluence of the currents of liquid modernity, globalization, local ethnic shifts, and employment instability, we are reticent to proclaim a model shoe that fits every foot. Two or three decades ago, American churches only had to struggle with receiving new members or a new pastor from a different region with a regional accent, however, now we must learn to minister with people of different races, languages, worldviews, and philosophical perspectives. Adding to the cultural mix, some immigrants come from countries which have three paradigms of inhabitants: pre-modern (ancient and so-called primitive, tribal societies, now called "indigenous peoples"), modern, and postmodern. I can remember attending a Christian college in the early 1980s with a classmate who converted from an African tribe. The fellow still had tribal markings scarred on his face but wore the typical American business attire with white dress shirt and tie. Now I wonder if postmodernity has led him to a third style and perspective. Understanding how culture and Christianity influence each other is indeed much more complicated than in the previous generation.

Neither modernity nor postmodernity provide a fail proof sail for guiding the church on the right course. The fluidity between modernity and postmodernity explains why Millennials and Baby Boomers just do not understand each other in the workplace or in church. Paradigmatic fluidity explains why such concepts as cell church, organic church, multi-site, and simple church have arisen in our time. Nobody can claim that any of these "models" are right for every church but borrowing the best ideas from specific models might increase our chances for better sailing. Every pastor and lay leader must figure out the best technique for his own ship and course. Imitating a megachurch model or some specific branding will most likely cause shipwreck for the smaller church in another context of ministry. Also, importing a supposedly successful American church's patterns and style overseas often makes unnecessary rigging for the indigenous vessel designed for a different climate. The worship forms, leadership styles, and organizational principles of modernity do not work for churches comprised of people from a postmodern and pre-modern cultural bent. On the one hand, church leaders must be ready to try new techniques and jettison the weighty cargo of old programs and approaches so they can take on new passengers. On the other hand, leaders and laity must hold on to their relationship with Christ who is their only secure anchor. They must not battle with each other while sailing on the same vessel, but they must work together as they depend on their Anchor who gives hope and security (Hebrews 6:9).